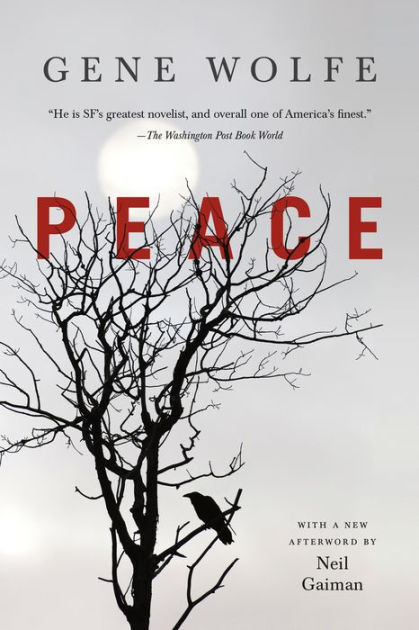

ISBN: 9780765334565

Date read: 14/05/2022

How strongly I recommend it: 10/10

Support your local bookshop by going to Bookshop.org to buy your copy (instead of THAT online shopping website…)

‘The elm tree planted by Eleanor Bold, the judge’s daughter, fell last night.’[1] What seems an otherwise perfectly mundane opening to a novel that appers on first reading to be a ‘sweet, gentle, meandering reminiscence,’[2] still haunts both my dreams and waking life in the many years since first reading this absolute diamond of a book.

You see, the true meaning of this line will not become clear to the reader until they reach page 209 (in the e-book edition), and that, I think, is the best metaphor for the genius of Gene Wolfe’s books, and what makes Peace such a monumental achievement for the novel form; you are never going to understand all of the secrets hidden within on a first reading. Only on a second or third time reading this book will you start making connections and discovering what this initially unassuming, but secretly chilling novel is really about.

On the surface, Peace is the memoir of Alden Dennis Weer, an elderly man who, due to a stroke that has affected his mobility, is confined to his large house and spends his time wandering through its many rooms while telling us his story. Emphasis should be placed on the ‘his’ part, as more than any of Wolfe’s other famously unreliable first person narrators, Den Weer is easily the most unwieldy.

‘It seems a pity that I have only thought of all that now, when there is no one to tell it to, but that may be for the best; there are many questions of that kind, as I have observed, to which people would sooner not know the answers.’[3]

This line, which appears very early on in the novel, is a perfect example of our narrator’s unreliability. He has already decided that we don’t want to hear about a certain thing, so he’s not going to bother telling us. We as readers are going to have to be crafty and find out some other way to get the information, and the best way is to try and intuit what it is that Weer is not telling us, or what he is letting slip when telling us about something he thinks is inconsequential. It also quickly sets up that Weer is not above lying to us. ‘Not always. Not even mostly. Just when it’s convenient for him to do so.’[4] This is where the real enjoyment of the novel takes hold, with Wolfe positioning us as detectives, and reading the book becomes like taking part in a thrilling puzzel game.

Even a sequence as straightforward as a visit to the doctor becomes a mystifying sequence that demands investigation:

Dr. Van Ness is slightly younger than I, very competent-looking in that false way of medical men on television dramas. He asks what seems to be the matter, and I explain that I am living at a time when he and all the rest are dead, and that I have had a stroke and need his help.

“How old are you, Mr. Weer?”

I tell him. (My best guess.)

His mouth makes a tiny noise, and he opens the file folder he carries and tells me my birthday. It is in May, and there is a party, ostensibly for me, in the garden. I am five. The garden is in the side yard, behind the big hedge.[5]

And suddenly we are at Den’s garden party for his fifth birthday. This will probably be the first of many times that the reader will be confused and forced to question exactly what is going on. This is the intended effect, however, and the reader must press on as the mysteries pile up, because the key thing about Peace that some attentive readers will come to understand is that all of these seemingly unrelated stories are connected and each one informs another.

A throwaway comment early on in the story will be revealed by a sentence hundreds of pages later, in one of the many stories, tales or anecdotes that Den Weer relates to us. I am probably making all of this sound overly difficult to decipher, but it is a complete joy. Wolfe has indeed constructed the novel to function as an elaborate puzzle, but trust me, all of the clues and solutions are right there in the book. All you need to do is to connect the dots. As Neil Gaiman says, when reading Wolfe we must, ‘trust the text implicitly. The answers are in there.’[6] He also said of this book in particular, ‘Peace really was a gentle Midwestern memoir the first time I read it. It only became a horror novel on the second or the third reading.’[7]

There are also at least 14 stories within stories in the book, all interpolated in the main plot of the novel and each one is a vital piece of the overall mystery, even if on the face of it they seem to be completely unrelated. Among them are a fairy story that Weer remembers from being a child, an account of an incident that happened at the factory where he worked as the result of a prank gone horribly wrong and even a Chinese fable.

I’ll also mention that the mystery of the true nature of the narrative, cheifly the circumstances regarding our narrator, is only the first mystery that you will solve. There are events in the book that are actually hidden within the text; implied events that take place and entire lines of inquiry that I completely missed, even after three readings, and can’t wait to go back in to uncover. This is when you’ll truly realise the meaning behind the title, because once you’ve read Peace, rest assured that your inquisitive mind will not find any for some time!

To finish, I will leave you with an excerpt that sets up one of my favourite mysteries in the novel, one that I only just deciphered on this reading, my third. You should read this passage the way you should be reading the rest of the novel; slowly, with care, asking questions, and completely and utterly engrossed.

‘This house has grown larger, not smaller. (Nor is it falling down- not yet.) I wonder now why I asked for all these rooms- and there seem to be more and more each time I go exploring- and why they are so large. This room is wide, and yet much longer than it is wide, with two big windows along the west side looking into the garden, and along the east side a wall that shuts out the dining room, and the kitchen, and my den, where now I never go. At the south end is the fieldstone fireplace (which is why I live here; it is the only fireplace in the house, unless I have forgotten one somewhere). The floor is flagstone, the walls are brick, and there are pictures between the windows. My bed (not a real bed) is before the fireplace where I can keep warm.’[8]

Sweet dreams.

You might also like…

- How To Read Gene Wolfe by Neil Gaiman – I highly recommend giving this short piece a read before reading any of Gene Wolfe’s books. It’ll take you 5 minutes, and it’s a perfect introduction as well as a nice little primer to get you ready and into the reading mindset you should be adopting while reading Wolfe’s masterful work.

[1] Gene Wolfe, Peace, (New York; Orb Trade 2012), P.1

[2] P.268

[3] P.3

[4] P.269

[5] P.6

[6] https://www.sfsite.com/fsf/2007/gwng0704.htm

[7] https://www.sfsite.com/fsf/2007/gwng0704.htm

[8] P.12